When the Nazis Tried to Bring Animals Back From Extinction

Their ideology of genetic purity extended to aspirations about reviving a pristine landscape with ancient animals and forests

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/a4/87a4c573-006e-48c2-9df7-daa77ecf6fa2/tur_zherberstein_pol_xviw_small.jpg)

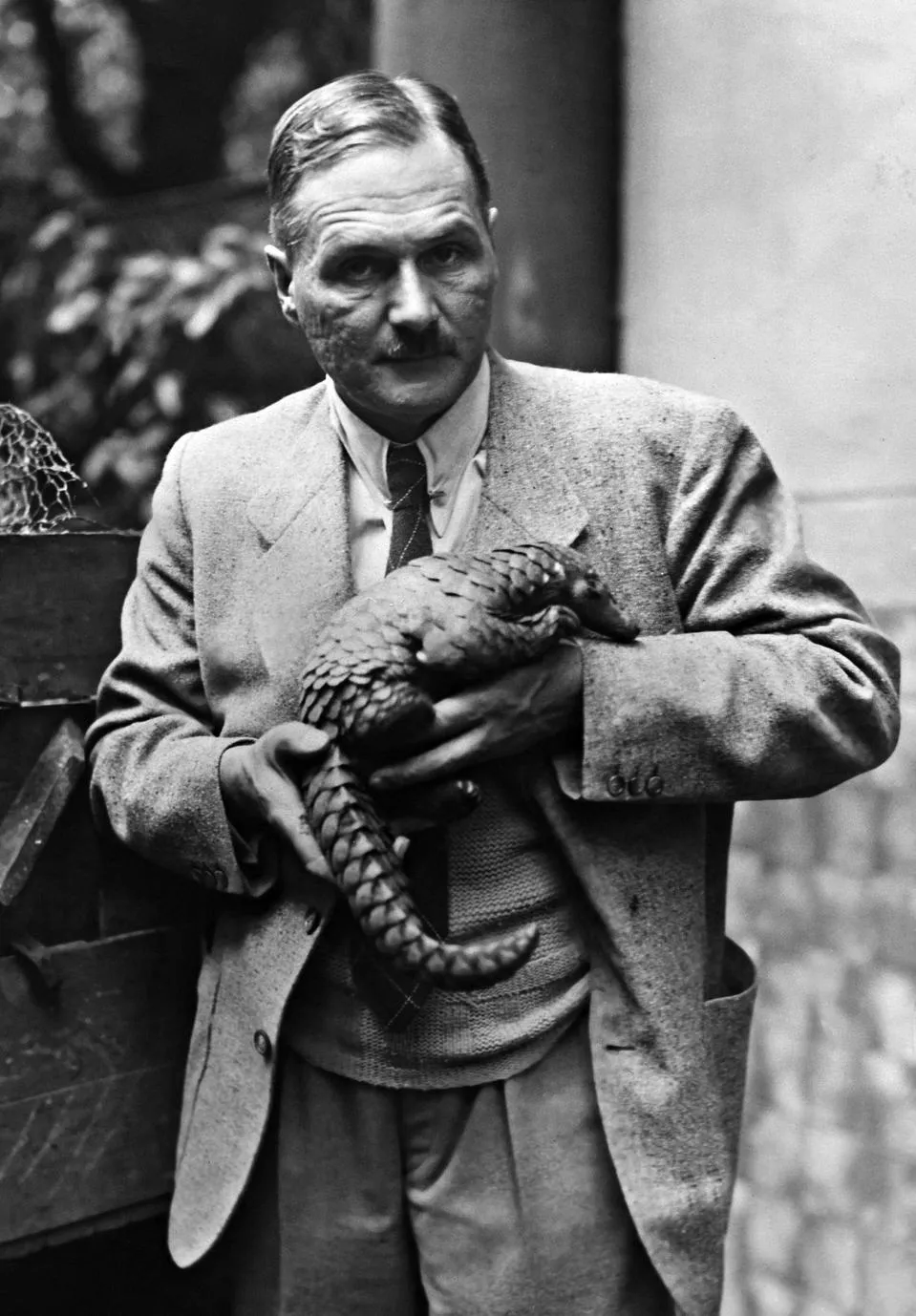

Born to the director of the Berlin Zoo, Lutz Heck seemed destined for the world of wildlife. But instead of simply protecting animals, Heck had a darker relationship with them: he hunted and experimented with them.

In the new movie The Zookeeper’s Wife (based on a nonfiction book of the same title by Diane Ackerman), Heck is the nemesis of Warsaw zookeepers Antonina and Jan Zabinski, who risk their lives to hide Jews in cages that once held animals. All told, the couple smuggled around 300 Jewish people through their zoo. Not only was Heck tasked with pillaging the Warsaw Zoo for animals that could be sent to Germany, he was also at work on project that began before the Nazis came to power: reinvent nature by bringing extinct species back to life.

Lutz and his younger brother, Heinz, grew up surrounded by animals and immersed in animal breeding, beginning with small creatures like rabbits. At the same time that the boys learned more about these practices, zoologists around Europe were engaged in debates about the role of humans in preventing extinction and creating new species.

“It was kicked off by all kinds of what we would consider quite weird experiments. People were trying to breed ligers and tigons,” says Clemens Driessen, a researcher in cultural geography at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands.

While breeders’ imaginations ran wild with thoughts of new species to create, closer to home, European bison, known as wisent, were going extinct in the wild. Scientists began to consider the role of zoos could play in keeping the species alive—and in Germany, to combine those answers with theories about the supposed “purity” of long-gone landscapes.

Should wisent be revitalized using American bison as breeding stock? Would the resulting offspring still be considered proper bison? As they grew older, the Heck brothers were immersed in these same questions.

According to an article written by Driessen and co-author Jamie Lorimer, Heinz saw the extinction of the wisent as the natural progression of the result of nomadic tribes overhunting. His brother, on the other hand, became more and more interested in what he considered to be “primeval German game”—an interest increasingly shared by Nazis who sought a return to a mythic German past free of racial impurities.

In his autobiography Animals: My Adventure Lutz describes being fascinated by animals he associated with that mythical past, especially wisent and the formidable aurochs.

Aurochs were large, horned cattle that went extinct in 1627 from excessive hunting and competition from domesticated cattle. The brothers believed they could recreate the animals through back-breeding: choosing existing cattle species for the right horn shape, coloration and behavior, then breeding them until they had something approximating the original animal. This was before the discovery of DNA’s double helix, so everything the brothers looked to for information on aurochs was from archaeological finds and written records. They believed that since modern cattle descended from aurochs, different cattle breeds contained the traces of their more ancient lineage.

“What my brother and I now had to do was to unite in a single breeding stock all those characteristics of the wild animal which are now found only separately in individual animals,” Heck wrote in his book. Their plan was the inverse of Russian experiments to create domesticated foxes through selective breeding—rather than breed forward with particular traits in mind, they thought they could breed backwards to eliminate the aspects of their phenotype that made them domesticated. (Similar experiments have been picked back up by modern scientists hoping to create aurochs once more, and by scientists trying to recreate the extinct quagga. Researchers disagree over whether this type of de-extinction is possible.)

The brothers traveled the continent, selecting everything from fighting cattle in Spain to Hungarian steppe cattle to create their aurochs. They studied skulls and cave paintings to decide what aurochs should look like, and both claimed success at reviving aurochs by the mid-1930s. Their cattle were tall with large horns and aggressive personalities, capable of surviving with limited human care, and in modern times would come to be called Heck cattle. The animals were spread around the country, living everywhere from the Munich Zoo to a forest on the modern-day border of Poland and Russia.

But despite their shared interest in zoology and animal husbandry, the brothers’ paths diverged greatly as the Nazis rose to power. In the early 1930s, Heinz was among the first people interned at Dachau as a political prisoner for suspected membership in the Communist Party and his brief marriage to a Jewish woman. Though Heinz was released, it was clear he would never be a great beneficiary of Nazi rule, nor did he seem to support their ideology focused on the purity of nature and the environment.

Lutz joined the Nazi Party early in its reign, and earned himself a powerful ally: Hermann Göring, Adolf Hilter’s second-in-command. The two men bonded over a shared interest in hunting and recreating ancestral German landscapes. Göring amassed political titles like trading cards, serving in many positions at once: he became the prime minister of Prussia, commander in chief of the Luftwaffe, and Reich Hunt Master and Forest Master. It was in this last position that he bestowed the title of Nature Protection Authority to Lutz, a close friend, in 1938.

“Göring saw the opportunity to make nature protection part of his political empire,” says environmental historian Frank Uekotter. “He also used the funds [from the Nature Protection Law of 1935] for his estate.” The law, which created nature reserves, allowed for the designation of natural monuments, and removed the protection of private property rights, had been up for consideration for years before the Nazis came to power. Once the Nazis no longer had the shackles of the democratic process to hold them back, Göring quickly pushed the law through to enhance his prestige and promote his personal interest in hunting.

Lutz continued his back-breeding experiments with support from Göring, experimenting with tarpans (wild horses, whose Heck-created descendants still exist today) and wisent. Lutz’s creations were released in various forests and hunting reserves, where Göring could indulge his wish to recreate mythic scenes from the German epic poem Nibelungenlied (think the German version of Beowulf), in which the Teutonic hero Siegfried kills dragons and other creatures of the forest.

“Göring had a very peculiar interest in living a kind of fantasy of carrying spears and wearing peculiar dress,” Driessen says. “He had this eerie combination of childish fascination [with the poem] with the power of a murderous country behind it.” In practical terms, this meant seizing land from Poland, especially the vast wilderness of Białowieża Forest, then using it to create his own hunting reserves. This fit into the larger Nazi ideology of lebensraum, or living space, and a return to the heroic past.

“On the one hand National Socialism embraced modernity and instrumental rationality; something found in the Nazi emphasis on engineering, eugenics, experimental physics and applied mathematics,” write geographers Trevor Barnes and Claudio Minca. “On the other hand was National Socialism’s other embrace: a dark anti-modernity, the anti-enlightenment. Triumphed were tradition, a mythic past, irrational sentiment and emotion, mysticism, and a cultural essentialism that turned easily into dogma, prejudice, and much, much worse.”

In 1941 Lutz went to the Warsaw Zoo to oversee its transition to German hands. After selecting the species that would be most valuable to German zoos, he organized a private hunting party to dispatch with the rest. “These animals could not be recuperated for any meaningful reason, and Heck, with his companions, enjoyed killing them,” writes Jewish studies scholar Kitty Millet.

Millet sees an ominous connection to the Nazi ideology of racial purity. “The assumption was that the Nazis were the transitional state to the recovery of Aryan being,” Millet wrote in an email. In order to recover that racial purity, says Millet, “nature had to be transformed from a polluted space to a Nazi space.”

While Driessen sees little direct evidence of Lutz engaging with those ideas, at least in his published research, Lutz did correspond with Eugen Fischer, one of the architects of Nazi eugenics.

But his work creating aurochs and wisent for Göring shared the same conclusion as other Nazi projects. Allied forces killed the wild animals as they closed in on the Germans at the end of the war. Some Heck cattle descended from those that survived the end of the war in zoos still exist, and their movement around Europe has become a source of controversy that renews itself every few years. They’ve also been tagged as a possible component of larger European rewilding programs, such as the one envisioned by Stichting Taurus, a Dutch conservationist group Stichting Taurus.

With scientists like the Dutch and others considering the revival of extinct wildlife to help restore disturbed environments, Uekotter thinks Heck’s role in the Nazi Party can serve as a cautionary tale. “There is no value-neutral position when you talk about the environment. You need partners and, [compared to gridlock that happens in democracy,] there is a lure of the authoritarian regime that things are all of a sudden very simple,” Uekotter says. “The Nazi experience shows what you can end up with if you fall for this in a naïve way.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)